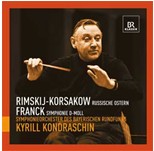

A new CD releasing featuring Kirill Kondrashin

The German label BR KLASSIK has just released a new CD devoted to the short collaboration between the Russian conductor Kirill Petrovich Kondrashin (1914-1981) and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, München. Apart from the fact that the numeric sound gives new power to the rendition of César Franck’s Symphonie en ré mineur (previously issued by Philips on LP recording), it additionnally gives the opportunity to discover one previously unpublished item, that is Rimsky-Korsakov’s Great Russian Easter Overture, Op. 36.

Incidentally, for those who already possess the brilliant recording of Tchaikovsky’s 1st Piano Concerto with the same orchestra and the young Martha Argerich, it brings the possibility of listening to the whole programme performed in Munich in February, 1980, and broadcasted by the Bayerisches Rundfunk.

Moreover, that new CD provides an opportunity of confronting two live recordings of Franck’s Symphonie en ré mineur conducted by Kondrashin, since the label TAHRA released a more than significant recording with the Royal Concertgebouw Symphony Orchestra, made in 1977. Knowing that Kondrashin first recorded that Symphony in Moscow in 1950, and had already been conducting it for several years, we can evaluate his performance of a work with which he had some 30 years of experience.

Last, but not least, this recording refers to one of the most fascinating periods of Kondrashin’s career. There are some things to say about it. Kirill Kondrashin defected from USSR to Netherland in November 1978, roughly about the same time as his friends Vishnevskaya, Rostropovich and Barshai did. But, in his case, that decision took an even more tragical aspect, since he died to soon to see Gorbachev’s Perestroika, the fall of Berlin’s Wall, and the return of the exiled artists. Actually, Kondrashin died amazingly soon after his defection, and had hardly enough time to live his new life as a free man, a free artist, and provide some incredible samples of the kind of artistic and professional mastery he had achieved by that time. Several fantastic recordings remain to give evidence of that, such as Beethoven’s 3rd Sympphony (Philips), Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazad (Philips), Sibelius’s 2nd Symphony (Tahra), Ravel’s Concerto pour la main gauche (Philips), Mahler’s 7th Symphony (Tahra), Stravinsky’s 4 Etudes for Orchestra (Berlin Classics), Lliadov’s Enchanted Lake, Tchaïkovsky’s 1st Symphony, Brahms’ 4th Symphony and Prokofiev’s 5th Symphony (all performed in Tokyo and issued by King Records, NHK, Tokyo), Brahms’ 1st Symphony (Philips), Shostakovich’s 9th Symphony (Berlin Classics and Philips), Tchaïkovsky’s Ballet Suites (Pickwick, with the Orchestre National de France), Borodin’s 2nd Symphony (Philips), Nielsen 5th Symphony (Philips), Ravel’s La Valse (Philips), Mahler’s 6th Symphony (NDRSO), not to mention his very last concert (Mahler’s 1st Symphony, a larger-than-life interpretation, after which he died of a sudden heart attack), recorded, and fortunately issued by EMI.

As a matter of fact, his untimely death prevented Kondrashin from being widely acknowledged as one of the foremost conductors in the world, since, after a tribute by Philips, consisting in several LP of live recordings with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, virtually all the labels discontinued his most important recordings, with the unique exception of his complete recording of Shostakovich’s symphonies. Today, many surprises still come from Russia (Melodiya), where his discography remain uncertain, and many riddles are still to be solved about his career, despite the parution of his biography by Gregor Tassie, Kirill Kondrashin, His life in music, last year. Absolutely no systematic effort has been made to restore his complete professional schedule, which is the only way to appreciate fully his legacy, and many of his records still prove impossible to obtain, just because they have been discarded by the music labels. Granted that the situation in Russia was even more complex, due to all the considerations surrounding his defection and his private life, we can infer that the somehow 300 published items recorded and sold by Kondrashin and roughly available are only the tip of the iceberg of his complete recording legacy, not to mention the 4 or five books he wrote (particularly one devoted to Tchaïkovsky’s complete symphonies), that prove totally elusive, even in Russia today.

All this make every new issue of a recording conducted by Kirill Kondrashin an event of importance, as far as the history of music and conducting is concerned. Incidentally, the present one stresses the fact that there still are other unpublished items featuring Kondrashin and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks : Beethoven’s 8th Symphony (an excellent recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra can be found in the States) or Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony (only published on LP by Philips). It would be an excellent idea to release them both on CD !

This would be enough to underline this CD’s interest, if it wasn’t also because of the quality of the interpretation of the works itself.

Let us begin with the technic of the recording. The sound technic of that CD is particularly great, and provides a feeling of limpidity, particularly with the strings, and a great balance in the tutti. Confronted to the previous LP releasing of Franck’s Symphony, the climaxes seem to be a bit less violent and explosive, but the sound’s beauty is even more bewitching.There has been some clean and smooth sound remastering, with a brilliant result, very similar to the orchestras’ sound obtained by Kondrashin during his late years.

The Overture by Rimsky-Korsakov, Op. 36 (dating from the same period as the Spanish Capriccio, Op. 34, and Sheherazad, Op. 35) is delivered in quite a different way as the explosive and magnetic interpretation by Hermann Scherchen issued by Tahra. Actually, some might be disappointed by the introduction, so soft, so careful, so balanced that it almost seems there is some hesitation in it. Kondrashin cultivates the transparency of the sound, as much as in his rendition of Lliadov’s Enchanted Lake, imposing and incredible discipline to all sections, particularly the brass and woods instruments, and making the strings sound with a pellucid quality and a definite timber in the smoothest pianissimo. For all who know Kondrashin well, this almost works as a signature. The tempo is rather restricted, cooler than in many interpretations. Kondrashin takes his time, and brings a progression as he only could do it. The explosion in the faster episode seems to be organic, and only there he gives the full power and coulours of the orchestra, always achieving incredible balance between the sections, where it is so easy to mix all together without any relief. If not as haunting as Scherchen’s reading, that one can stand as one of a man of refined taste and very high expertise. As a matter of fact, Kondrashin has always proved himself to be a foremost and particularly succesful interpreter of Rimsky-Korsakov, as all his recordings assert, from the complete Snegurochka with the Bolshoi, to his fantastic and orgiastic Sheherazad, not to mention his Piano Concerto with Richter, and the magnificent Spanish Capriccio recorded in the States in 1958. He also used to perform a Suite arranged from the opera Kitezh, which has been recorded in Ravinia, but yet not released…

Now let us examine the rendition of César Franck’s Symphonie en ré. As we said earlier, Kondrashin had an experience of more than 30 years with that work, which is particularly interesting by such a precise and hard working conductor. We can also confront that recording with the one issued by Tahra, which was made with the Concertgebouw Amsterdam. This is all the more interesting that Kondrashin had such a deep artistic relationship with the Amsterdam main Orchestra that almost everytime we can compare his recordings with that formation with recordings with other orchestras, the Dutch ensemble finishes in first position. This is widely demonstrated with such incredible recordings as Brahms’ 1st and 2nd Symphonies, Ravel’s La Valse, Tzigane and Rhapsodie espagnole (not to mention his legendary Daphnis et Chloé, for which we have no recording to confront with), Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Danses, Sibelius’ 5th Symphony and En Saga, Prokofiev’s 3rd Symphony, Shostakovich’s 4th and 6th Symphony, not to mention Skriabin’s 3rd Symphony, absolutely miraculous. In only very few cases did Kondrashin manage to do better with other orchestras, even with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, and the USSR State Symphony Orchestra, the two Russian ensembles with whom he enjoyed the closest and longest associations. This stresses the excellent standard of his performances in Amsterdam, and no doubt the recording of Franck released by Tahra is something to admire for the impeccable smoothness of the orchestra’s balance and coulours, the fluidity of the phrasings, the whole’s coherence.

However, the BR Klassik CD bears an exception, as regards this analysis. The performance of Franck’s Symphony is one of the most powerful, entrancing ever, equal only to that of the great French conductor Paul Paray. The introduction is ominous, not only piano, there is some magic here. There are some supernatural forces at work, and this feeling will never let you till the end of the performance. The explosions of the first theme is uttered with a kind of terror, and ponctuated by sinister brass interventions. A slight touch of rubato, more than in Amsterdam, allows a dramatic progression to the climaxes, and the second theme is never serene or quiet, always surrounded by forebodings of a tragic issue, which eventually clashes. One is bewildered by the way in which the conductor arranges all the rendition in a narrative way, as a very experienced story-teller, as a consummate actor. The development is both worked in clear touches of sounds and chords, as well as with heavy accents, and the final liquidation is particularly tense, even agonizing. Nothing romantic in this, nor handsome or trivial !

The ominous content of the first movement, which seems to evoke death, never leaves the second movement, which, as a result, gives an impression of an inexorable march in search of some hope, maybe that of Orest after having killed his mother, in search for Apollo’s purification. Nothing trifling, here, contrary to what the reviewers wrote after the world premiere of the work, but a suffering way. The associations between the different sections of the orchestra is really something to wonder at, and the Bavarian formation has hardly ever sounded so great. In fact, Kondrashin presents César Franck as Berlioz’ successor, particularly in the Symphonie fantastique, and it must be said that he is definitely right.

The last movement is something really terrifying. This is no longer music, no longer performance, this is sorcery, this is shamanism. All the sections are coached in order to graduate the climaxes in a cosmic progression, and we really have the feeling of hearing something absolutely new, and frightening. Right from the beginning, the brass sections don’t simply play a first call, they paint a hellish and agonizing stage setting, upon which medium parts, played by the strings stress the pulsating anxiety of a body. The main theme is nothing like handsome, but is played in a deconstructing way, as if the exposition were already a liquidation, with changing harmonical environment and exploded rhythmical patterns. Kondrashin really makes of that piece something of a sorcerer’s curse, or even fate’s curse itself. That movement had hardly received such a dark interpretation, even in the lighter passages in major chords, where the woodwinds and the strings transparency gives a pallid atmosphere rather than pacified. The major fanfares are always organised to prefigure deconstructing episodes, and the tension is always paroxistic. Generally speaking, Kondrashin obtains from the brass section features he rarely obtained with any orchestra, except the Concertgebouw itself. The effect is really devastating, all the more that the balance is always managed with the other sections. The recurence of the 2nd movement’s theme is particularly harrowing, and nothing like jubilatory.

The public at the concert in Munich felt that so much that, after a heavy and anxious silence, there came an immense and long wave of applause. The editorial decision of cutting the applause might be discussed, here !

Right after the concert, the Symphonieorchester’s staff decided to start procedures to propose Kondrashin to be appointed as Musical Director in replacement of Rafael Kubelik. Though the Russian conductor was delighted with that proposal, this was never to happen, since death took him away a few weeks before his official debut in his new function.

By the time he conducted that concert, Kondrashin often achieved such incredible happenings, even during public rehearsals. There was something of a wizzard by this man of exactitude and precision. It was as if freedom had opened a new way of expression in him. His Dutch wife told about his late concert : “I looked at Kirill and he was quite transparent, I don’t know how to say it, but it was as if a light was shining from inside… It was like a struggle between good and evil, I was sitting there with a chill in my spine, I heard what was going on, and it was so exciting.” (G. Tassie, op. cit., p. 281)

We really hope that the recording legacy of that brilliant conductor and foremost artist will be uncovered plainly very soon. There are still so many unpublished ones, such as Tchaïkovsky’s 6th Symphony with the Concertgebouw, or with the London Symphony Orchestra, or Shostakovich’s 8th Symphony with the Concertgebouw, or the complete symphonies by Tchaikovsky, Skriabin and Rachmaninov in Moscow… No video has ever been released of Kondrashin conducting any Symphony, which is simply a shame and a great loss for all musicians. And his books must be translated and published. There is still a lot to do to pay a due tribute to him !